Writing a family history is a rewarding activity that enables you to preserve the stories of your ancestors for future generations. As a professional genealogist and published author, I’ve seen many aspiring family historians struggle with how to get started, what to include in their book, and how to structure it. If you’re thinking about writing your own family history, here are my three key tips for success:

1. Determine the Scope

One of the most common mistakes people make when starting a family history project is trying to cover too much. It’s nearly impossible to write about every ancestor in your family tree in a single book.

Just think: we all have 8 great-grandparents, 16 2nd great-grandparents, 32 3rd great-grandparents, etc. And of course, many of us have discovered ancestors that go back much farther than that. Trying to include everything you’ve discovered can lead to overwhelm for both you and your readers. Instead, narrowing your focus will help you create a more engaging and manageable project.

Here are a few ways to define the scope of your family history:

Focus on a Single Ancestor

Instead of chronicling your entire family tree, consider writing about one ancestor’s life in depth. This could be an ancestor who led an interesting life, played a key role in history, or has left behind significant records and personal documents. Another option is writing several shorter ancestor profiles that can later become part of a larger book.

Focus on Your Most Recent Ancestors

A common scope for a family history is to focus specifically on your most ancestors. For example, one of my students is currently working with her two siblings to create a family history telling the story of their parents and four grandparents.

Tell the Story of an Immigrant Generation

Many families have powerful immigration stories. You might choose to write about the ancestors who first arrived in a new country, detailing their journey, struggles, and accomplishments. This type of family history is especially compelling when paired with historical context, describing what life was like in their homeland, why they chose to leave, and how they adapted to their new surroundings.

Trace a Specific Lineage

Another option is to focus on a single surname or family line, tracing the story of a particular branch of your family. For example, you could document the descendants of your paternal grandfather or explore the matrilineal line of your family, focusing on the women’s contributions and experiences.

Highlight a Specific Time Period

If you have extensive records from a particular era, you could center your book around that period. For instance, you might write about your family during the Great Depression or World War II, incorporating both genealogical research and historical context.

By determining the scope of your project early on, you can ensure that your family history remains focused, compelling, and achievable.

2. Choose the Format

Once you have determined the scope of your family history, the next step is to decide on the format. There are several ways to organize and present your research, each with its own advantages and challenges:

Formal Genealogical Formats

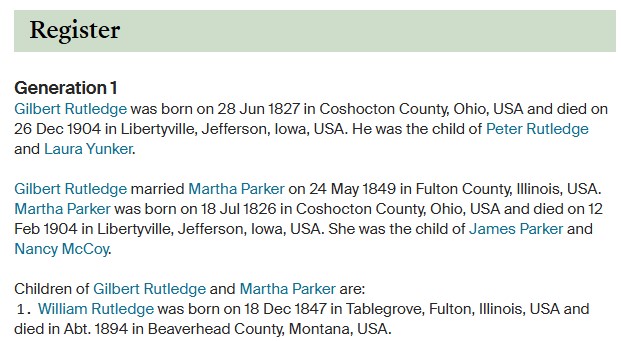

- Register Format: This structured format follows a genealogical numbering system to present descendants in a clear, organized manner. This is ideal for those who want a scholarly and reference-style family history.

- Ahnentafel (Ancestor Table) Format: This format organizes ancestors by generation in a numbered list, making it easy to follow direct ancestral lines.

- Descendancy Format: If you want to focus on the descendants of a single ancestor, this method presents information starting with the earliest known ancestor and working forward through generations.

Tip: You can create register, ahnentafel, or descendancy reports automatically in Ancestry if you have a subscription to Pro Tools.

Narrative and Storytelling Approaches

Many family historians prefer a narrative format that blends genealogical research with storytelling. This allows you to bring ancestors to life by incorporating anecdotes, letters, diaries, and historical events. Instead of just listing names and dates, you can describe what life was like for your ancestors, including their struggles, triumphs, and relationships. For example, instead of stating that your ancestor was a farmer in Ohio, you could describe what daily farm life was like in the 1800s and how your ancestor adapted to changing agricultural practices.

Photo Books

If you have a large collection of family photographs, a photo book might be a great format for your family history. This works exceptionally well for more recent generations, where photos, newspaper clippings, and documents are more readily available. A well-curated family photo book can include captions, short descriptions, and even excerpts from family letters or interviews. This is an excellent way to create a visually engaging family history that appeals to a broad audience.

Choosing the right format depends on the type of information you have, your writing style, and your intended audience. If you’re not sure which format to choose, consider combining multiple approaches. You could, for example, use a narrative format but include an Ahnentafel chart as an appendix for reference.

3. Choose Your Audience

Before you start writing, it’s important to consider who your audience is. This will help you shape your writing style, depth of detail, and distribution plan.

Private Family Distribution

If your primary audience is your immediate and extended family, your family history can be informal and personal. You might include more anecdotes, humorous stories, and family traditions. The book could be printed in a small quantity for family reunions, holiday gifts, or keepsakes for future generations.

One advantage of writing for a private audience is the ability to include personal and sensitive family stories that you might not want to share publicly. You can also be more flexible with your format, focusing on what is most meaningful to your family members.

Public Distribution and Publishing

If you want to publish your family history for a broader audience, you need to approach the project with a more polished and professional tone. A well-researched and well-written family history could appeal to others researching the same surname, descendants of your family, or historians studying the time period in which your ancestors lived.

There are many self-publishing options available, from print-on-demand services like Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) and IngramSpark to more traditional small press options. If you go this route, consider adding citations and source references to enhance credibility and appeal to genealogical researchers.

A public family history book may also attract interest from local historical societies, genealogy libraries, and researchers, expanding its reach beyond your immediate family.

Tip: Understanding your audience from the beginning will help you make crucial decisions about tone, content, and distribution.

Writing a Family History: Final Thoughts

Writing a family history is an enriching experience that preserves your family’s legacy for future generations. By determining a realistic scope, choosing the right format, and identifying your audience, you can create a compelling and meaningful record of your ancestors. Whether you opt for a detailed narrative, a structured genealogical report, or a visually rich photo book, the key is to tell your family’s story in a way that resonates with your readers.

Remember, a family history is more than just names and dates—it’s a story of resilience, adventure, and legacy. Start writing today, and give your ancestors the voice they deserve.

- What Is a Second Cousin? - October 29, 2025

- What Does a Genealogist Do? - June 19, 2025

- Choosing the Best DNA Test for Genealogy Research - June 17, 2025